The increase in electricity demand due to artificial intelligence and data centers has been widely discussed over the last few months. But it’s not just data centers that are driving load growth. Most decarbonisation stories are also linked to electrification. This demand growth presents several investment opportunities, especially across utilities, mining, and industrials.

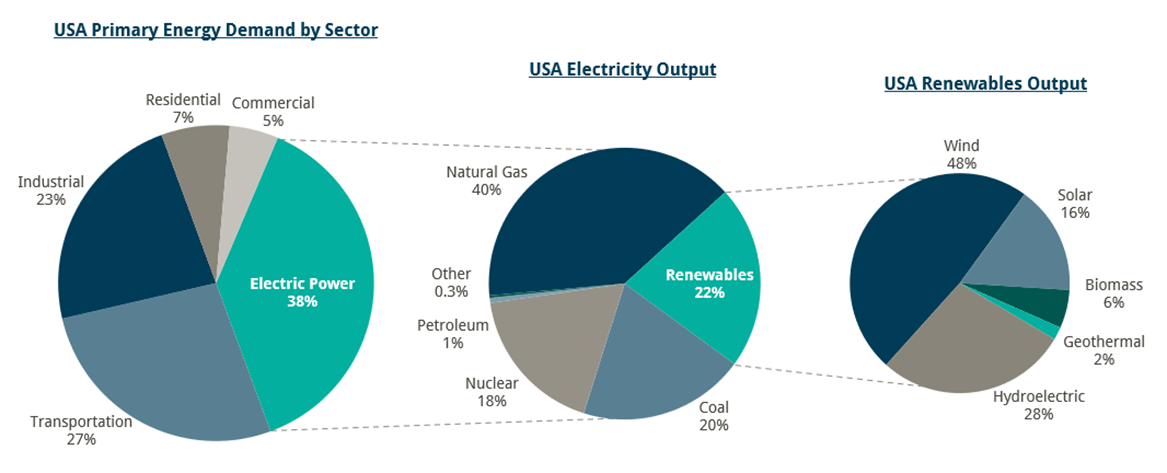

The majority of electricity demand increases, led by these data centers, have been seen in the US. It’s important, thus, to start with a background on the US’s energy demand. Electricity accounts for ~38% of primary energy demand in the United States today, with this number poised to rise after being flat for the last 15 years. Most of this demand is sourced from coal and natural gas, with renewables making up only 22% of electricity production. Within the renewables sector, wind and solar energy are usually top of mind, but one-third of renewable capacity in the USA is hydroelectric, which will not significantly grow. This implies a rapid increase is required in renewables capacity if hyperscalers plan to source marginal electricity demand from renewables.

On a global basis, the International Energy Agency (IEA) projected in 2022 that electricity demand would begin growing again at 1-2% per year after a decade of being flat. This number rises to ~3% when we incorporate the growth that has recently emerged due to data centres. Realistically, it is difficult to achieve more than 3% growth if the supply cannot meet the demand, and this problem is further complicated if the electricity must come from green sources.

Although data centres have driven the conversation thus far, there are four other sources of electricity demand that should be considered.

Electric Vehicles: Despite falling manufacturers’ share prices over the past two years, demand for EVs continues to rise. EVs are more energy efficient than combustion engines and are expected to be a significant driver of electricity demand by the end of the decade. For context, the average EV uses ~3 MWh of electricity per year, and the average household uses 4 MWh of electricity in the UK and 10 MWh in the US per year. This suggests that EVs are likely to significantly affect household demand regardless of location in the coming years.

Heat Pumps: Heat pump sales continue to rise globally, despite manufacurers’ falling share prices, implying heat pumps will be a notable source of electricity demand going forward. Although much more energy efficient than natural gas, a switch to heat pumps would roughly double electricity consumption on a household level, particularly in cold climates.

Industrial Decarbonisation: The decarbonisation of steel, aluminium, chemicals, and other manufacturing facilities is likely to be another source of baseload electricity demand as decarbonising these processes typically involves substituting natural gas and coal for electricity. Electrifying steel production globally would require ~1% of the world’s electricity, while electrifying aluminium would require ~3% of global electricity. These numbers are compelling and not far behind the IEA’s projections for data centre usage at 3-4% of global electricity in a full electrification case.

Air Conditioning: Air conditioning penetration in Europe is low today at 19% in contrast to the US at over 90%. Unfortunately, hotter summers have resulted in air conditioning slowly becoming the standard in Europe, and this penetration rate is expected to rise in the next decade. If we add up the electricity demand growth from air conditioning in Europe by 2030, it is comparable to the expected demand growth from data centres. Globally, air conditioning is the largest source of incremental electricity demand growth, especially in emerging markets.

What investment opportunities does this create?

Transmission: We think there will be an enormous investment cycle in electricity grids relative to natural gas grids. While natural gas prices may rise, we think consumer natural gas demand in developed markets will continue to fall. In our opinion, valuations do not yet reflect this structural dynamic.

Electrification equipment: We think industrials with exposure to electrification equipment will see stronger growth relative to industrials with other end markets. Investors should pay particular attention to electrification names that have both pricing power and volume growth as their customers scale up.

Transition metals: Copper, nickel, lithium, and other transition metals continue to have strong demand stories. The prices of these metals will fluctuate on supply, but underlying demand growth will create investing opportunities for quality assets. In contrast, we believe iron, zinc, and coal have limited growth outlooks, with high prices generally driven by supply disruptions.

Location is key: Data centre investment has historically not focused on cheap or green power as a determinant. We see this in Ireland, which has Europe’s largest data centre hub due to low taxes but no access to cheap electricity sources. Ireland has limited hydro, no nuclear energy, and no domestic fossil fuel resources. The country can build offshore or onshore wind, but does not have cheap baseload green electricity.

We compare energy transition and data centre investing to real estate – the key is location, location, location. It is important to understand which regions have an appetite for data centres, as we suspect government and utility involvement will be significant and could create divergent outcomes. The S and G of ESG appear to have been forgotten in the data centre discussion, but it will be interesting to follow where data centres are supported by local communities and governments and where there is pushback. In our view, it is vital to examine this dynamic in relation to power prices as they are variable across regions as well.

The rise in baseload electricity demand due to data centers will exacerbate the challenges of the energy transition in the medium term and continue to cause stock-specific dispersion. From a global perspective, we hope that in the longer run, artificial intelligence and rising power demand can be used to improve efficiency in energy use and improve living standards, but the result in the near term will be challenged by upgrading electricity grids and rising capital spending.