Unfortunately, being a sovereign with an open capital account also means that domestic accounts can freely respond to this environment by investing money abroad. There are many reasons for that: from not having enough domestic assets (small & open surplus economies, like Norway or Australia), to not having attractively priced assets at home (Japan before Covid, for example). Japan now is peculiar because it has plenty of attractively priced assets at home, but there is a belief that 1) those assets will become even more unattractively priced, so there is no reason to rush, and 2) the currency will keep weakening. In other words, it is a confidence game which can be broken by clear policy signals from the government.

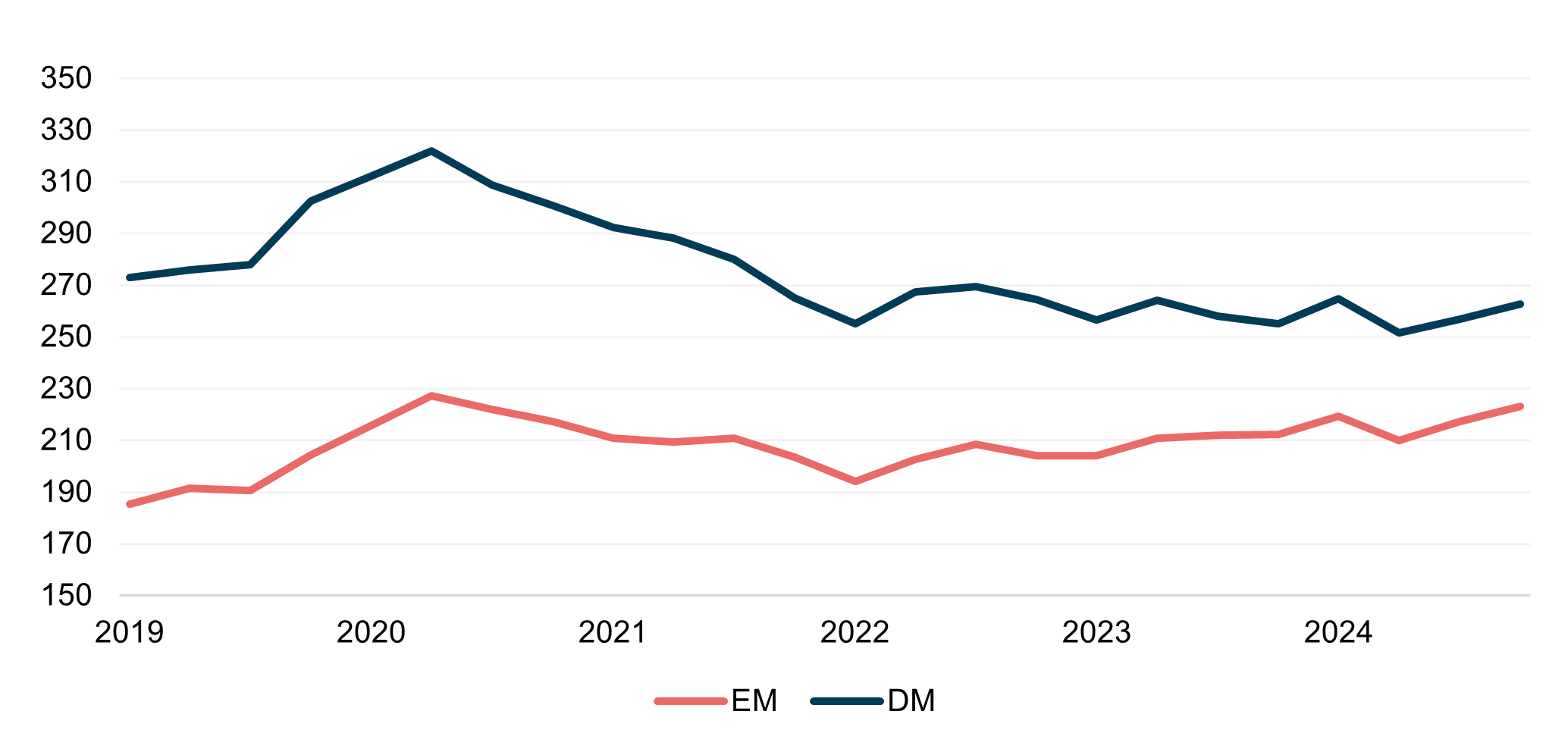

What are those signals? The one that the market has been focusing on the most is on the fiscal side: stabilise the budget and reduce overall net issuance of JGBs. But net issuance has been trending lower recently due to fiscal consolidation efforts, and even though net issuance for the latest fiscal year is higher, net issuance in the long end is still lower – and it is the long end where yields have risen the most. So, fiscal is an issue, but not the main one here.

The signal that can potentially stabilise everything is an explicit policy of a stronger JPY backed by a more hawkish BOJ. If that fails, add incentives to encourage domestic investment to stay home. There is a significant difference between foreign outflows and domestic outflows – the latter have a ‘home bias’ by default. But in the case of the Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF), for example, there isn’t one, as 50% of its assets are invested abroad (more than for EU or US pension funds, for example). It is much easier to get domestic capital to stay home than to get foreign capital to invest there.

How do we get there? Start with intervention in the currency – Japan has more than enough foreign assets, plus, judging by Bessent’s latest comments, the US will be happy to accommodate. Move Japan up the confidence curve to get capital flowing back to it. I do not buy the view that investors have no reason to put money in a ‘demographically challenged’ country like Japan because of limited domestic opportunities: look at similarly large surplus but much smaller economies which have absolutely no problem attracting capital, like Switzerland and Singapore, for example.

It is a policy choice. Sovereign countries create their own ‘bond vigilantes’ – the latter have power only on paper, so they can be as easily put into oblivion by the right policies.