Unless you are deep in the woods of it, like we are, you may be forgiven for not having noticed that Emerging Markets (EM) have outperformed Developed Markets (DM) year-to-date (YTD). Investors and the financial media alike have ignored EM for the last decade, and perhaps rightly so, as it has underperformed DM over this period. But this year – among all the hype about AI and how it is benefiting primarily US Tech stocks – EM Bonds, Credit, and FX have all done better than their DM counterparts (ironically, Chinese internet companies’ profits have jumped by nearly 50% so far this year, while their share prices are down around 10% – the opposite to what has happened to some of the largest US Tech firms.

We think there are six reasons to back up this claim:

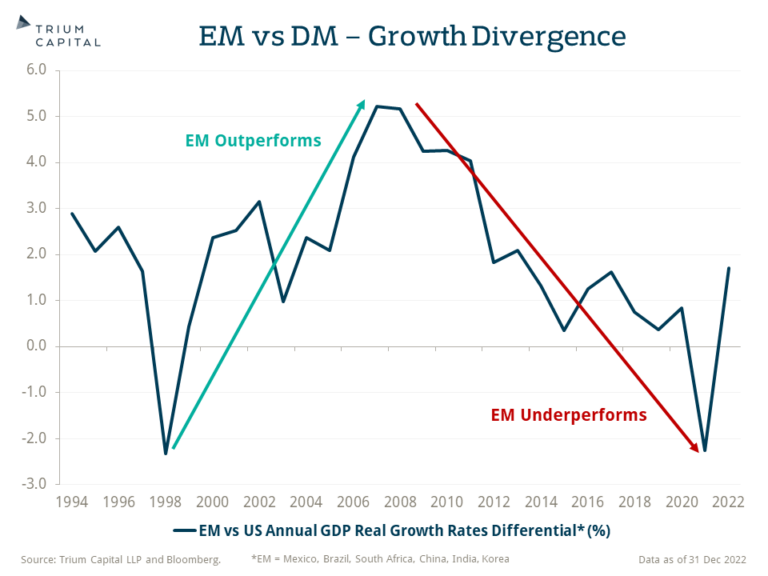

1. Growth Divergence

In the period post the Asian/Russian crisis in late 1997-1998 until the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, EM growth trended above DM growth, and EM outperformed DM. In the period that followed, the opposite happened. We believe this latest cycle, characterised by more than a decade of DM QE followed by a heavy dose of Covid stimulus, is now at an inflection point and is likely to turn in favour of EM.

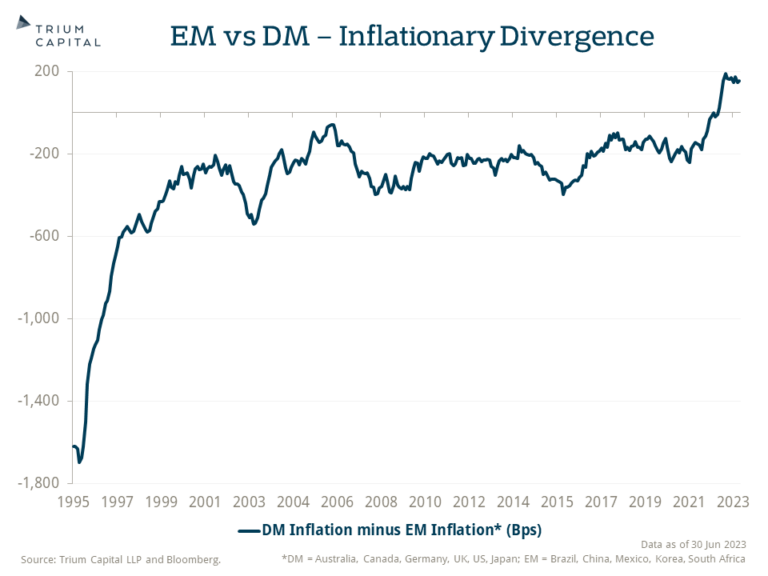

2. Inflation Divergence

The Russia-Ukraine conflict may have changed the global supply chains much more than Trump’s tariffs on China before that, at least when it comes to energy. When coupled with the effect of DM’s policies (see our previous post) on Aggregate Demand, the result was a burst of DM inflation never seen in the last 40 years. It is not surprising, then, that DM inflation surpassed EM inflation for the first time in the summer of last year.

3. The Institutional Credibility Divergence

As a direct result of the past policies, particularly when it also comes to their belated response last year to the rise in inflation, there is an argument that DM Central Banks have lost some institutional credibility. At the same time, EM countries have built up institutional credibility by granting their Central Banks autonomy to run inflation-targeting frameworks. This development, if we are right in our judgement (as there is no specific data to prove the case), can have a much longer-lasting positive structural effect on EM vs DM.

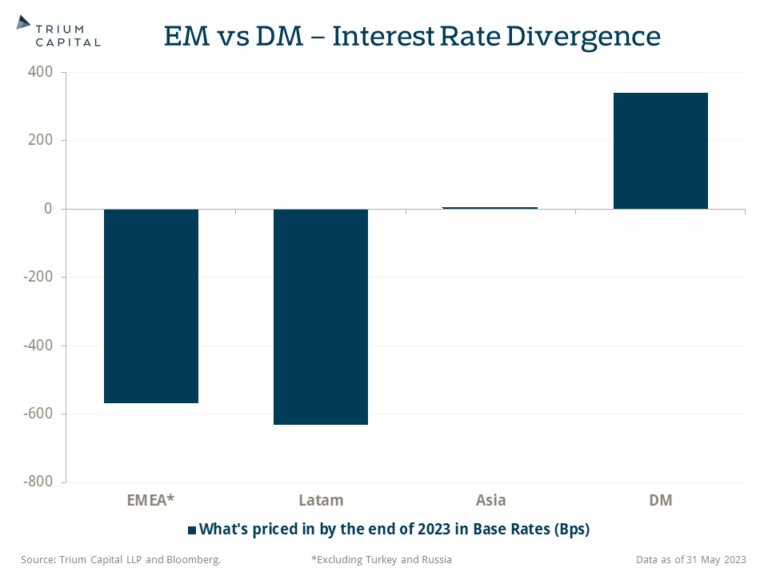

4. The Interest Rate Divergence

The large majority of global rate hikes YTD (there are about 90 of them) have been done by DM Central Banks. All the rate cuts, on the other hand (17 of them), were in EM. This latest divergence builds on the ones before – EM is pivoting to easy monetary policy, while DM continues on their hawkish path (DMs that paused have been forced to resume hikes – BOC, RBA and others – Norges, BOE – have increased the pace of hikes). There are about 1200bps of rate cuts priced in for 2023 year-end in EM and about 340bps of hikes for DM (including Turkey, where more than 1000bps of hikes are prices, and Russia, 200bps of hikes, offset those other cuts in EM).

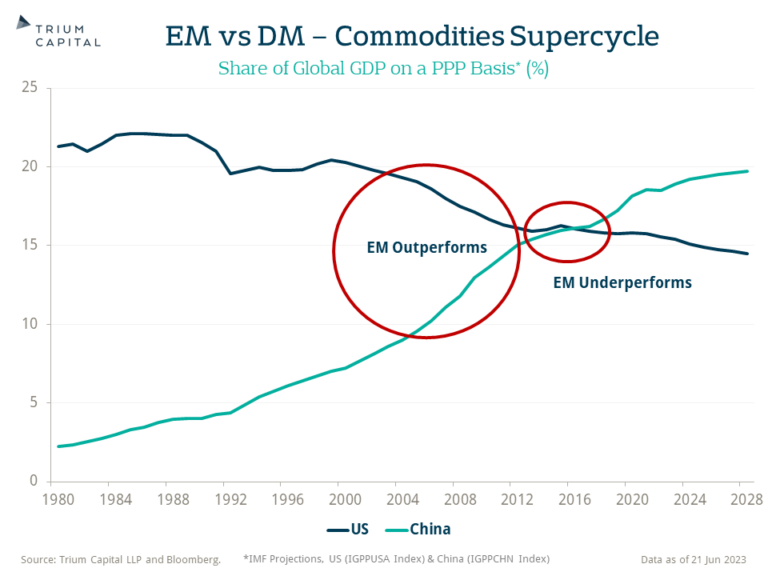

5. Commodities Super Cycle to Resume

We think China’s rise as the dominant economic power in the world is not a fluke – Size matters. While we acknowledge that demographics will be a drag on population growth, high literacy/education levels and the advance of General Artificial Intelligence (GAI) can offset the decline in production on the supply side by raising productivity. The right institutional framework can sustain household purchasing power and thus maintain consumption growth levels stable on the demand side. The rise in China (moving up the manufacturing value chain) comes along with a DM impetus to re-industrialise after years of general neglect (CHIPS and Sciences Act, Bipartisan infrastructure law, Inflation Reduction Act in the US; Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) and a Net-Zero Industry Act to facilitate the green energy transition in Europe). This should put a bid on all commodities going forward. The recent geopolitical developments, however, may have improved the Terms of Trade for EM at the expense of DM and, in the process, generated a trend whereby countries prioritise securing their commodity supply chains rather than amassing more financial reserves.

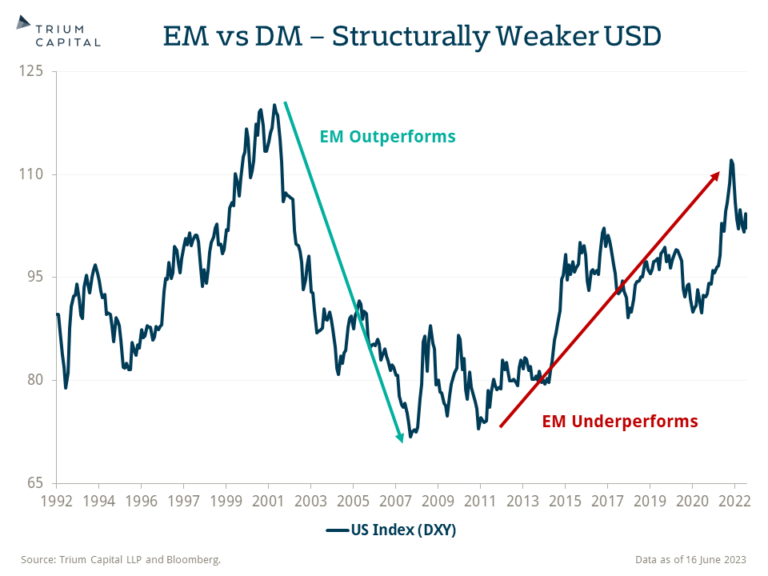

6. Structurally Weaker USD

The USD is likely to remain the undisputed reserve currency in the next decade, but its superiority as the dominant global trade currency is challenged by the rise of the Renminbi (CNY): about one-third of China’s cross border trade transactions are invoiced in CNY; more and more of global trade has gone through in a non-USD currency. Financial flows, being multiple times larger than trade flows, matter more in the currency market, but at some point, the latter is likely to affect the former and, thus, global currencies standing. Moreover, the reshuffle of China’s government this March was followed by the same at the PBOC, the result of which is likely to be a much more proactive fiscal policy at the expense of monetary policy, ensuring a stable CNY serving as a magnet for foreign flows as well.

It has been difficult to be an EM bull in the last decade or so, but it might be just the time to think about becoming one now.