Gold. The investor’s best friend in helping to preserve value over centuries. And now potentially on the cusp of major bull market.

Gold preserves its value due to its elemental scarcity. Rarity at an elemental level protects it against human ingenuity trying to undercut its value. Diamonds lack the same benefit as at a chemical level a diamond is simply common carbon atoms tightly bound together in a crystalline structure. As tough as diamonds are, replication involves much easier challenges in tweaking a chemical structure rather than splitting the atom through nuclear engineering.

The technology of lab-grown diamonds has started to affect their status as a girl’s best friend. In their recently aborted merger, the one thing that BHP and Anglo American could agree on was that the famous De Beers diamond business needed to be jettisoned. Both parties wanted to focus on the similar, but less rare, elemental copper. What is true for diamonds is true for NY Taxi medallions and any of the myriad of shorter-lived stores of value here on our planet. Nothing shines like gold.

An elemental defence against human progress

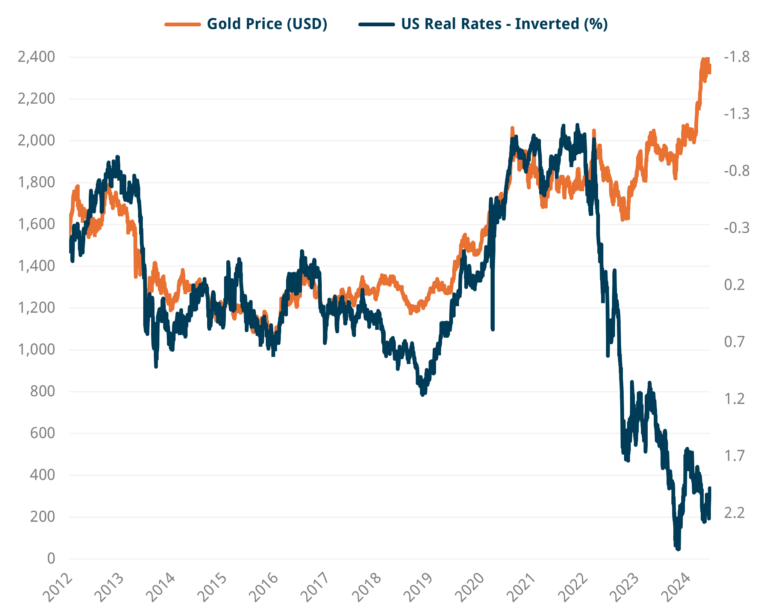

The value of gold often traces out a path dictated by US real rates. The real rate can be thought of as the return on capital that can be earned through betting on human ingenuity. There is no yield on it, so when real rates are high, investors want to funnel money into the economy and out of gold to benefit from these high returns. When real rates are low, investors seek haven in gold, seeing value in its elemental defence against human progress.

Gold's relationship to real rates has changed

Gold has ceased to follow real rates since early 2022. As real rates pushed higher amid the Fed’s belated attempt to fight inflation, gold ought to have struggled. While gold did not rally, it did hold its value in the face of real rates moving quickly through zero and up above 2%. Then, in late 2023, as the pace of the real rates increase calmed down, gold continued to carve its own path and rallied substantially.

Source: Bloomberg & Trium Capital LLP

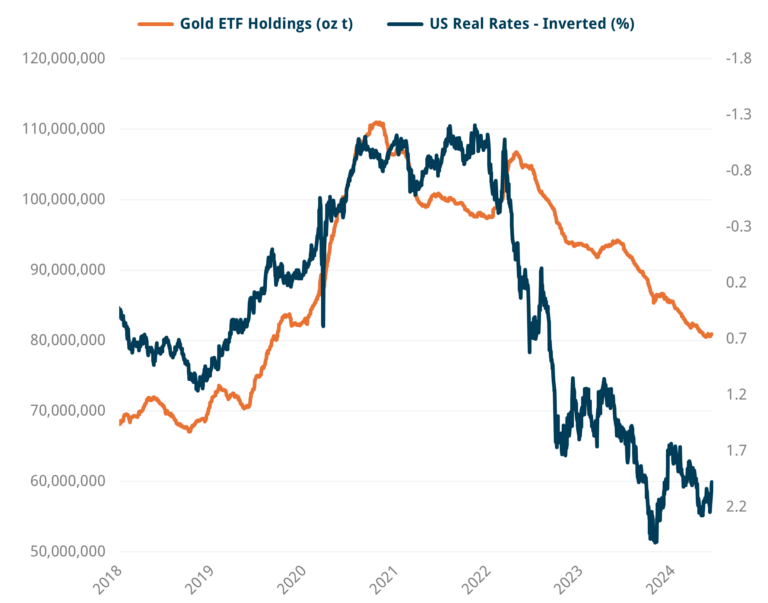

The question is, what changed? Why did real rates stop explaining gold price movements? It certainly wasn’t advances in nuclear engineering! It wasn’t the behaviour of Western investors either; they divested from gold ETFs as real rates increased and the perceived opportunity in financial assets grew. If we assume that Western gold ETF flows are broadly representative of total flows, then investors have not changed their behaviour. This means Western investment flows are no longer in the driving seat of determining the gold price.

Source: Bloomberg & Trium Capital LLP

Nor is the culprit Indian jewellery and investment demand. The opportunistic nature of Indian gold buying remains inversely correlated to the gold price, with buyers stepping in on dips, taking advantage of prices passively rather than driving it.

Official buying steps up

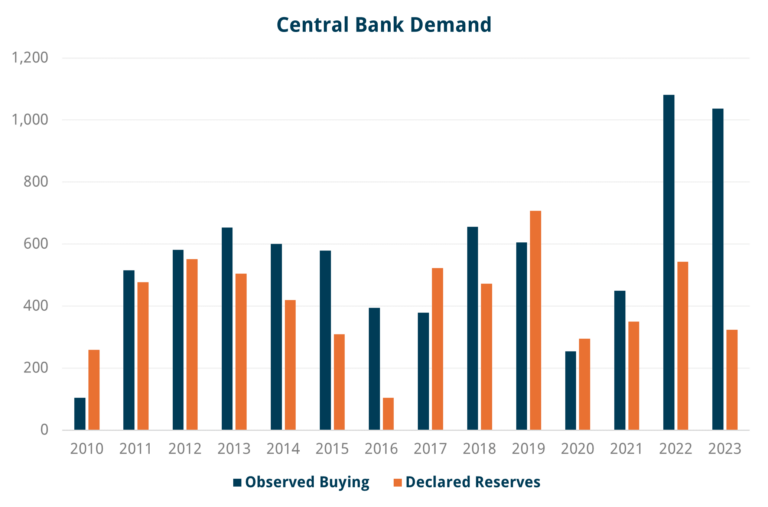

The change is an increase in central bank accumulation. 2022 saw the largest net purchases in years, a major change from the large drawdown of reserves by Western central banks over the last three decades.

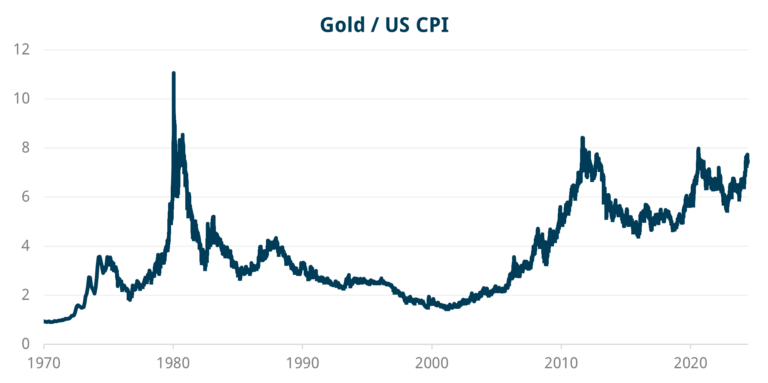

This story started with the West removing itself from the shackles of the gold standard it struggled to maintain in the 1970s. Its release saw gold surge to all-time highs in real terms in 1980. These high valuations were a starting point for the poor performance of gold in the 1980s and 1990s. Throughout the 1980s, Paul Volker took care of inflation with Thatcher and Reagan overseeing an increase in economic growth driven by deregulation. Gold reserves were no longer necessary to underwrite currencies, and gold’s poor performance relative to currency reserves was considered a drag.

Gold price deflated by US CPI

Source: Bloomberg & Trium Capital LLP

Eventually, the low was marked in 1999 with Gordon Brown’s decision to sell over half the UK’s gold reserves. The government’s announcement ahead of the fact panicked the market and eventually led to the Washington Agreement on Gold, where European countries affirmed that gold should remain an important part of global reserves and together coordinated to sell no more than 400 tonnes annually from September 1999 to September 2004. A second version of the treaty was signed in 2004, but by this time, opportunistic buying by emerging market (EM) central banks was already underpinning the market.

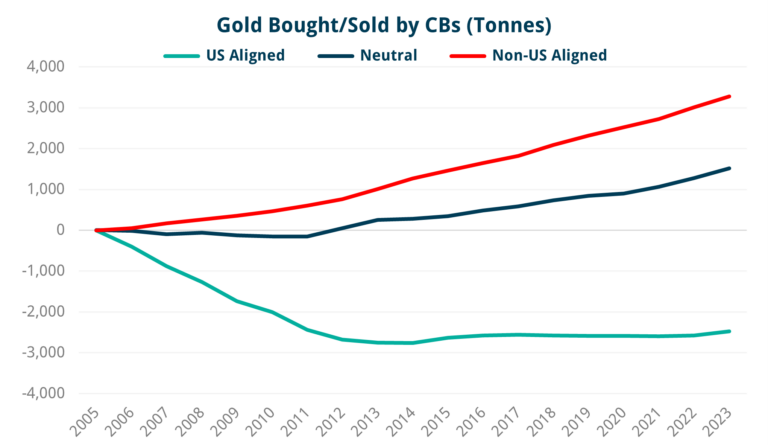

Source: World Gold Council, Bloomberg & Trium Capital LLP

Buying was scaled up significantly as Trump imposed tariffs on China in 2017, then further following the breakout of Russia’s war in Ukraine in early 2022. This seems to be the key geopolitical juncture for a shift in the behaviour of the gold price.

Europe joined the US and the rest of the developed world (without exception) in putting sanctions on Russian banks and freezing their overseas assets. This even included the historically neutral Switzerland and Austria. The move sent shockwaves throughout the world as countries that were not aligned with the US feared their assets would be similarly confiscated or frozen.

The US even froze the Dollar accounts of Afghan nationals upon exiting the country. Even if you worked for the US your assets still got frozen, showing that it is not only sovereign states who are at risk but individuals within them.

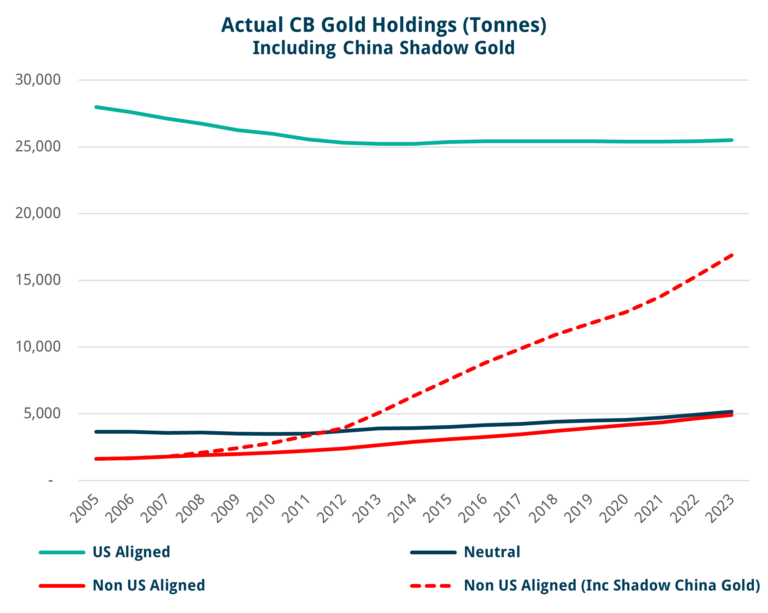

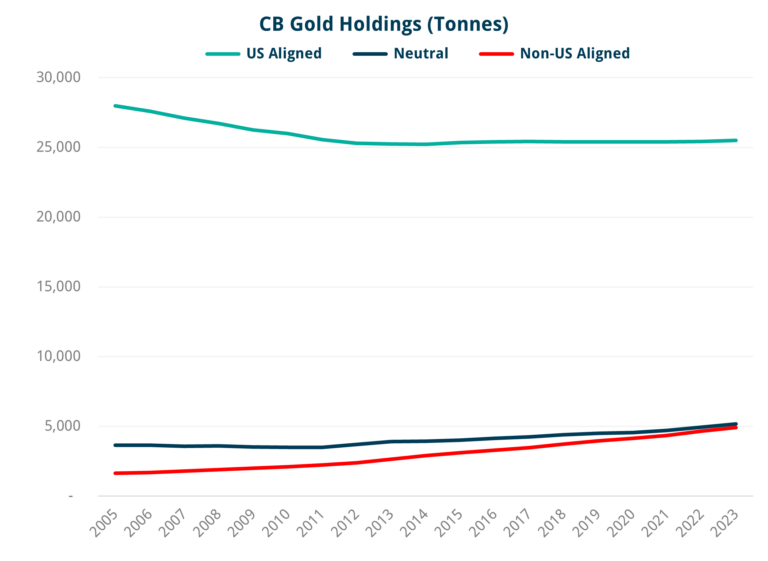

The chart below shows the official gold holdings of global central banks split by affiliation. Countries have been categorised based on their attitude to the Ukraine war. Countries that have joined sanctions against Russia are labelled as US-aligned countries. Those who have avoided taking sides are neutral. Countries that have adopted a more supportive stance towards Russia (North Korea, Iran, China, Belarus) are considered non-aligned countries.

Source: World Gold Council, Bloomberg & Trium Capital LLP

Despite the significant accumulation of gold by non-aligned banks, the amount of gold held is still small relative to the West. This means pushing up the gold price reflates Western balance sheets more. Non-aligned countries need to be subtle in their buying; it is not in their interest to drive the price up quickly. So why are they buying in such force?

There are two answers to this question. The first answer is that China is weak. The second answer is that China is lying.

China is forced to accumulate gold so long as it suppresses consumption

China accumulating more gold does not herald the demise of the US dollar, US hegemony or power, regardless of what those who sell you newsletters are keen to tell you. It points to weakness rather than strength. They don’t have other options.

China is a top-down autocracy that represses not just the democratic votes of their citizens but economic “votes” too. It represses consumer spending power and redirects surplus income into more investment and more capacity. This policy lowers the prices of consumer goods and outcompetes countries that can’t carry out this economic repression as effectively. It results in persistent surpluses in the balance of payments. This surplus doesn’t balance over time like you would expect to see in a freer economic model. So long as the policy remains, so will the surplus.

A redistribution of economic power would break the Chinese state and so will only happen in the case of an economic collapse. Hence, the surpluses will likely continue. Where to invest these surpluses is fast becoming a major problem for China. Other countries antagonistic to the US, like Russia, also have this problem, as do autocratic neutral countries like Saudi Arabia (who also have concerns about the safety of its investments in the US and allies).

A lack of safe assets elsewhere

The vast majority of safe liquid assets globally are in Western sovereign bond markets. No countries outside this alliance have the status of safety or the liquidity required. In terms of equities, the picture is similar.

The lack of liquid financial assets outside the West leads China towards outbound Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). This means doing business in jurisdictions that lack political stability and have weak legal systems that are vulnerable to politics and can’t/won’t enforce contract law. As the West has discovered, even with the full might of the international institutions behind them, claims tend to fall secondary to local politics. And much like with the old adage about banks; if you owe $100 it is your problem, if you owe $100m it is their problem. These markets just don’t have the efficiency or scale to absorb large amounts of capital.

China found this in its first iteration of the One Belt One Road (OBOR) scheme. Many investments have been overbudget, unfinished or abandoned. While debt investments technically have a call on equity ownership in the case of infrastructure projects, in practice, this is considered anathema to sovereignty and ultimately unenforceable.

Despite this, China is still investing immense amounts in outbound FDI, taking the view that the return of 50 cents on the dollar is a better deal than taking the expropriation risk in Western assets.

In terms of outbound FDI, the situation for China is worse than for Western countries given it doesn’t play ball with the IMF and does not have a blue water navy to browbeat others. That’s why China has spent most of its energy nearer to home, where it has more sway, and the West has less.

That 50-cent return on the dollar is not even scalable as you ramp up investment. The more you spend, the worse the quality of the project and the less money you can expect to recoup. China at home can recoup gains at a total economy level from infrastructure investment, through taxes and better growth, even if a direct return on capital is hard to structure. That is not the case abroad.

Gold is a frustrating asset to accumulate as it is less liquid and useful than US treasuries and leads to higher volatility in the end goods you want to hold your purchasing power against. It is only when you consider gold accumulation as an option versus expropriation risk, or a 50-cent return on FDI, that China’s policy starts to make more sense.

There also isn’t enough gold. The current account surplus of China alone is equivalent to the entirety of global gold production at today’s prices. And, of course, they aren’t the only buyer. The bull case for gold does not rely on China recycling the proceeds from selling down its current Western bond holdings; not wanting to add to existing expropriation risk is enough, and there is not much else to buy.

Hidden sovereigns

Gold is a murky market with clear data only extending to what is mined rather than who owns what. Partly, this is because those attracted to gold want to evade attention for one reason or another. That said, there is enough information to put together a rough picture. We have a fair idea of how much central banks have been buying in aggregate, as these purchases tend to be done in the West and using dollars. These purchases are considered “monetary gold” for use as recognised reserve assets by central banks, accepted by credit rating agencies and international institutions like the IMF. Buyers through this route are easy to track in aggregate as they tend to be significant orders in much larger bar sizes than other investors. They also are exempt from customs declarations on both ends, something that masks purchases from trade statistics but informs the seller what the gold will be used for.

China’s official sector likely holds significantly more gold than is officially reported. China’s central bank seems to follow the international rules for reserve accumulation but often declares its holdings with a large delay. In the last couple of years, as estimated by Metals Focus, the buying pace by central banks has doubled, but the increase in the sum of all gold reserves claimed has stayed around the same level. China declaring buying late in April 2009, announced 454 tonnes of gold bought over a six-year period. They did the same with 604 tonnes in 2016. History (and market chatter) tells us that of the 1,250 tonnes of undeclared gold purchases over the past two years, the vast majority is China. That would mean their true reserves are closer to 3,000 tonnes rather than their stated reserves of 1,750 tonnes.

Source: Metal Focus, World Gold Council, Bloomberg & Trium Capital LLP

This is still only half the story. Unlike the opaque old secrets of how much gold is held in Fort Knox or in Swiss vaults, most of China’s gold has been bought recently. All locally produced or “privately” imported gold in China goes through the Shanghai Gold Exchange (SGE). Net imports of gold into China have been around 24,000 tonnes since the exchange was established in 2008. This is large compared to central bank reserves, even if you think the true reserve number is understated.

China has a myriad of state institutions that are known to buy gold, including the army, whose gold reserves are a state secret. The army even has its own division, the “Chinese People’s Armed Police Force Golden Troops”, solely focused on gold exploration, surveying, and transport.

These purchases are not monetary gold and are likely bought in Yuan on the SGE. Market insiders suggest that half of the net imports of gold since the SGE opened are on behalf of government entities. Likely, none of these 12,000 tonnes are monetary gold held by the PBOC. Instead, it forms a shadow reserve of around 12,000 tonnes of gold bought on the open market and held by various opaque institutions.

The chart below shows that Chinese FX reserves have been static since 2016 at around $3.2trn. A deepening mystery given the current account has been in constant surplus throughout the period. A mystery somewhat resolved when you realise that China’s official gold holdings are likely worth around $1trn more than commonly believed, value that is not reflected in the chart below.

Source: Bloomberg & Trium Capital LLP

We estimate that China’s true state holdings of gold are the world’s largest. That means non-aligned countries are not far behind the volumes of gold held by the West. As it reaches parity with the West, China’s desire to purchase gold in the shadows could come into the light more quickly than the market expects.