A Negative (NIRP) – or Zero (ZIRP) – interest rate policy works best when the private sector is running a deficit. Low interest rates then provide borrowing relief and may cushion the strain on households’ and corporations’ balance sheets (especially if financial assets also rise as a result). However, when the private sector is running a surplus, zero or negative interest rates are a drain on the private sector’s income and, depending on their asset allocation, could be a net negative for the overall balance sheet.

In addition, a sustained period of NIRP may create an environment of not only low expectations for economic growth but also disinflation. This is almost independent of the mechanics of monetary transmission, and it also affects decision-makers’ economic behaviour. Sadly, Japan falls under all of the above categories when it comes to the harmful effects of NIRP. The good news is that this seems to be changing.

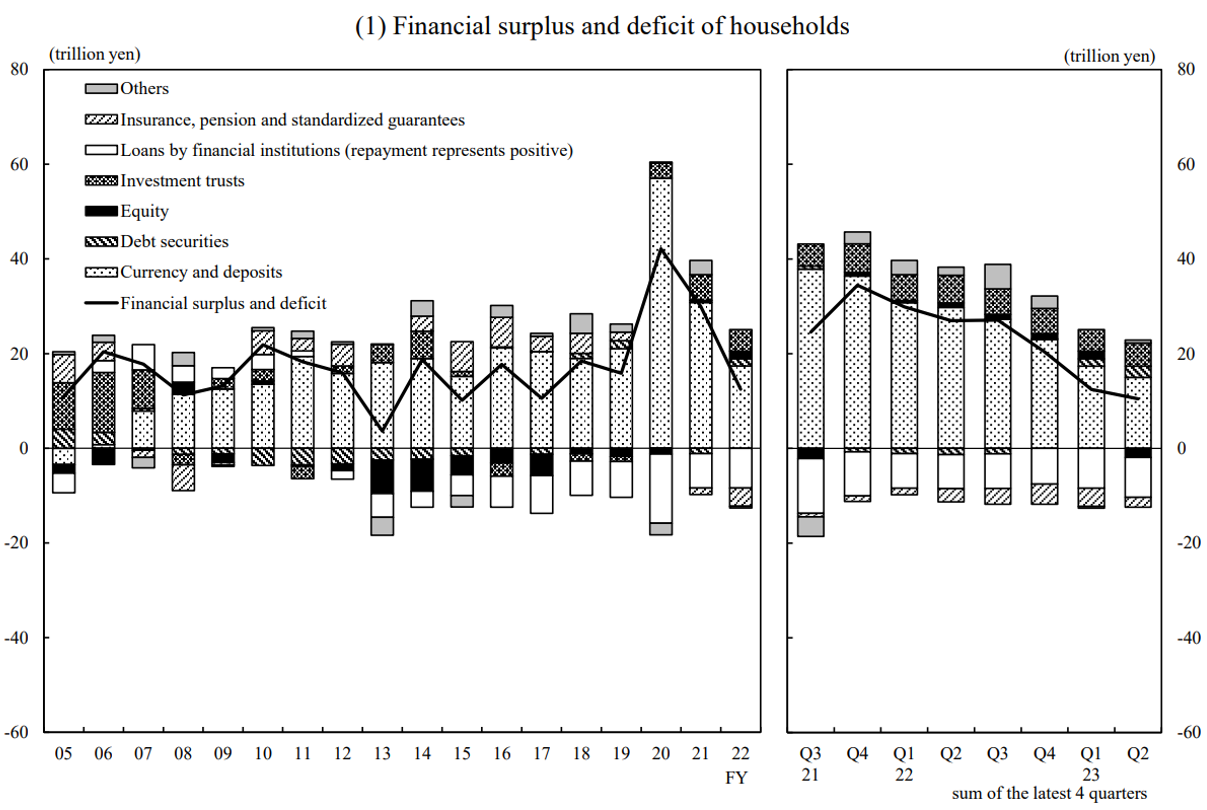

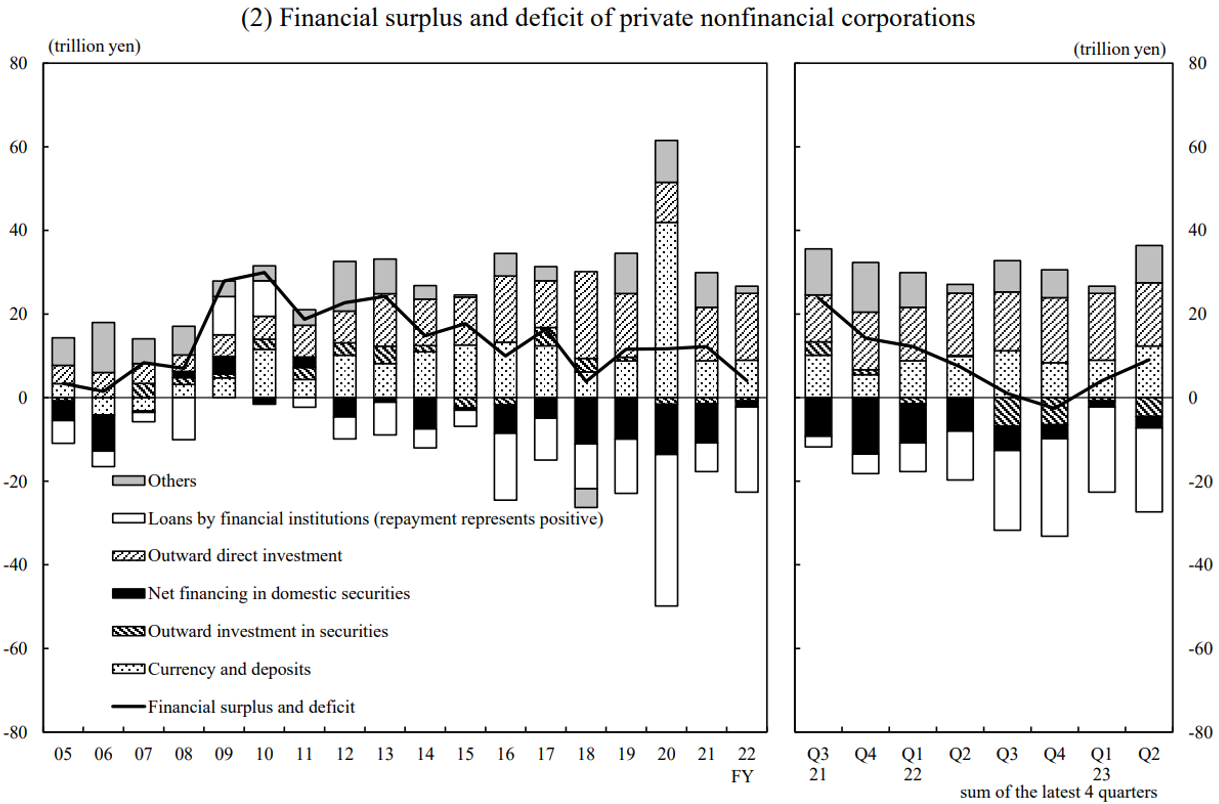

The private sector in Japan has been running a surplus since at least 2005, BOJ data shows. That is especially true for Japanese households whose balances never got below zero (it got close to it in 2013, though). Japanese corporates have generally lower positive balances and have, on occasions, dipped below zero as in Q4 2022.

Source: Bank of Japan, Research and Statistics Department: “Flow of Funds for Q2 2023” Preliminary Report, September 2023 (https://www.boj.or.jp/en/statistics/sj/sjexp.pdf)

In fact, Japanese households have been running surpluses even before 2005. They were especially large in the 1980s. However, non-financial corporations were running a large deficit in the 1980s, offsetting the household surplus. After the 1990s crash, the household sector surplus substantially declined while the corporate sector deficit gradually improved. It was the government sector, which generally runs a deficit, that saw a substantial increase in its deficit starting in the early 1990s1.

In this context, as initially implemented by the Bank of Japan (BOJ), ZIRP made sense – the private sector needed to deleverage (at the expense of the government sector). However, by the time the BOJ introduced NIRP in 2016, deleveraging was over. The government sector, however, was still running substantially large deficits. Hence, the negative interest rates of 2016 were not really necessary for the private sector. By 2023, they may have become an overkill. The ZIRP has helped the government sector roll over its massive debts, but what has really helped in this regard was arguably the yield curve control (YCC) policy.

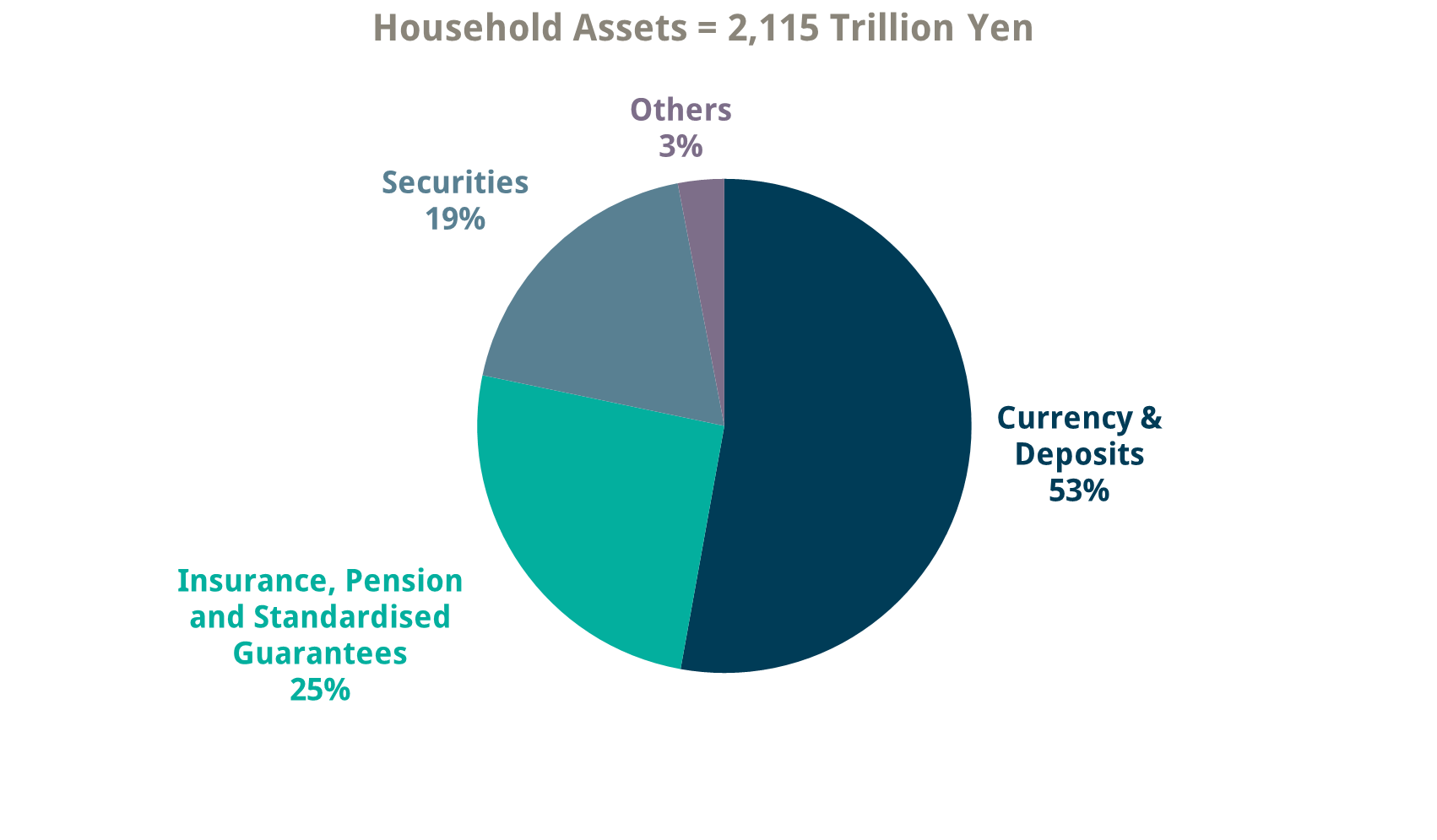

A negative interest rate of -10bps makes little difference compared to a policy of zero interest rates when it comes to monetary transmission. Still, it may have huge negative consequences on how the private sector behaves over the long run. That is on top of the direct negative effect on households’ income, as Japanese households hold more than 50% of their assets in deposits. In hindsight, the Japanese economy may have fared better if the BOJ had kept rates at zero instead, with YCC in place.

Source: Trium Capital LLP and Bank of Japan, Research and Statistics Department: “Flow of Funds for Q2 2023” Preliminary Report, September 2023 (https://www.boj.or.jp/en/statistics/sj/sjexp.pdf)

This takes us to the present. This week, the BOJ’s deputy governor Himino highlighted the benefits of ending NIRP, particularly for Japanese households and corporates2. In light of Prime Minister Kishida’s record low approval rating3, this suddenly opens another avenue of possible monetary policy action – an earlier-than-expected end of NIRP. The BOJ’s governor, Ueda, also followed up later while speaking in Parliament, hinting that there may be some changes to monetary policy into year-end4.

“It will become even more challenging from the year-end and heading into next year…We will work to properly communicate and conduct appropriate policy.”

Ironically, an early exit from NIRP may spur the private sector to borrow more. Firstly, on expectations that rates have hit bottom and are finally on the rise, so locking in low rates, and secondly, from a behavioural point of view, on expectations that the economy is improving and that opens opportunities to deploy capital. Also, ironically, it may mean that BOJ may exit NIRP before YCC.

In fact, in an environment where the front end of the yield curve is on the rise, there is an argument to be made that YCC is needed even more – especially if the goal is to manage the Japanese government’s enormous debt pile. At the same time, with the BOJ’s balance sheet at 125% to GDP (with the second largest, the European Central Bank, at only around 50%), there seems to be little room left to expand it further. Unless an early NIRP exit reignites the private sector’s ‘animal spirits’, which spurs economic growth. It is possible, but the market may need some time to be convinced.

A much early NIRP but a much later YCC exit? At this point, it seems to us that this is a decision no longer dependent on economic data per se, but on balance sheet effects – both on the private sector (households and corporates) as well as the public sector (the government and central bank).

______________

1https://www.boj.or.jp/en/research/brp/ron_2005/ron0503a.htm

2https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/boj-must-carefully-time-design-exit-low-rates-deputy-gov-himino-2023-12-06/

3https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Japan-PM-Kishida-s-approval-rating-sinks-to-new-low-of-30-Nikkei

4https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-12-07/boj-s-ueda-says-handling-policy-set-to-get-tougher-from-year-end