The easing of US sanctions on Venezuelan bonds stands as a tangible indicator of a recalibrated approach. While initial sanctions were imposed due to political and humanitarian concerns, lifting restrictions acknowledges the necessity for nuanced engagement, balancing the imperative of internal stability in Venezuela with global energy-related concerns. Finally, after a long time, the “Barbados Accord”, as it has been referred to, has pushed Maduro’s government to promise “free and fair” elections next year and the release of several political prisoners.

María Corina Machado, a self-proclaimed “centrist”, claimed victory in a recent opposition primary held days after the Barbados deal was struck. Although she was banned from running for office for being an outspoken critic of President Maduro’s government, given the new accord, she will likely face him in next year’s Venezuelan presidential election. Whether her victory will be positive for Venezuelan macroeconomics or bond valuations is harder to say. After years of enduring financial repression and grappling with deep-seated economic imbalances, Venezuela’s economy now stands at a critical juncture. The lifting of sanctions alone could act as a substantial growth catalyst for Venezuela’s economy by directly boosting oil production.

While Maduro has little motivation to permit Machado to participate in fair elections, we aren’t convinced that the US will promptly reinstate sanctions. However, market participants will be monitoring the Machado-Maduro confrontation and will be looking for material change in the US government discourse towards Venezuela.

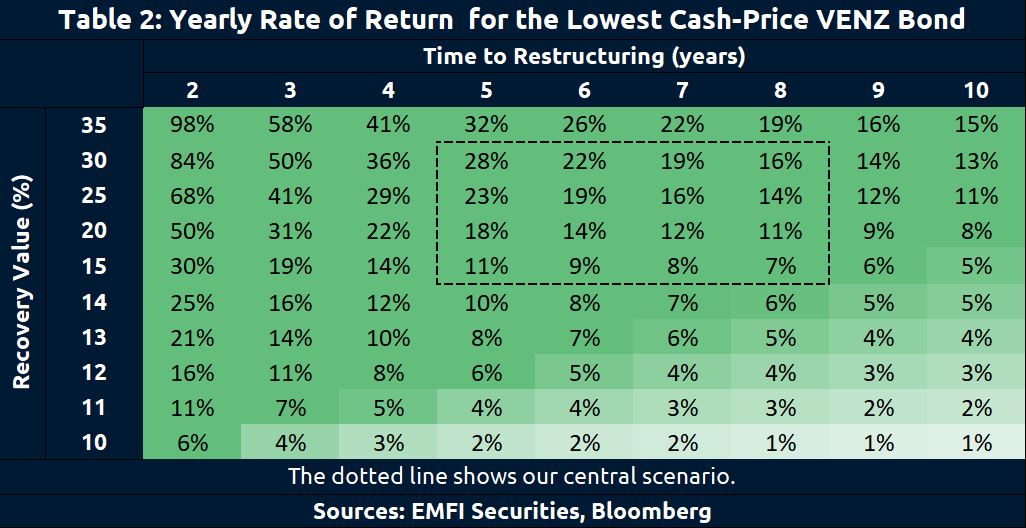

Sanctions being lifted mark the first significant catalyst for Venezuela. Bond prices were up between 70% and 100%. We still think there is more to the Venezuela story, but the trade has changed. It is essential to have a firm grip on potential recovery values and be cognisant of market technicals.

Restructuring – When and How?

The recovery narrative for Venezuelan and PDVSA bonds will depend on when and under which circumstances (how) the restructuring will occur. “When” is still uncertain, as it requires the US government to lift financial sanctions (not included in the recent accord) and recognise whichever government is in control.

The “how” is equally essential and also uncertain. The Venezuelan economy and its debt-carrying capacity strongly depend on the recovery of oil production via the value of the country’s exports. If sanctions were fully lifted, and if the US recognised a legitimate representative of the Venezuelan state, oil production could rise significantly. The rise would remain limited, given the lack of a solid investment environment. However, a more centrist opposition government would likely fare much better in this regard, enabling larger amounts of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to lift production.

Trying to appropriately assess debt sustainability in the country in this scenario is a difficult task. However, with the first main catalyst (sanctions) out of the way, one can have a better view on recovery values. Hence, we should look at oil production and take a view on potential leverage in the economy.

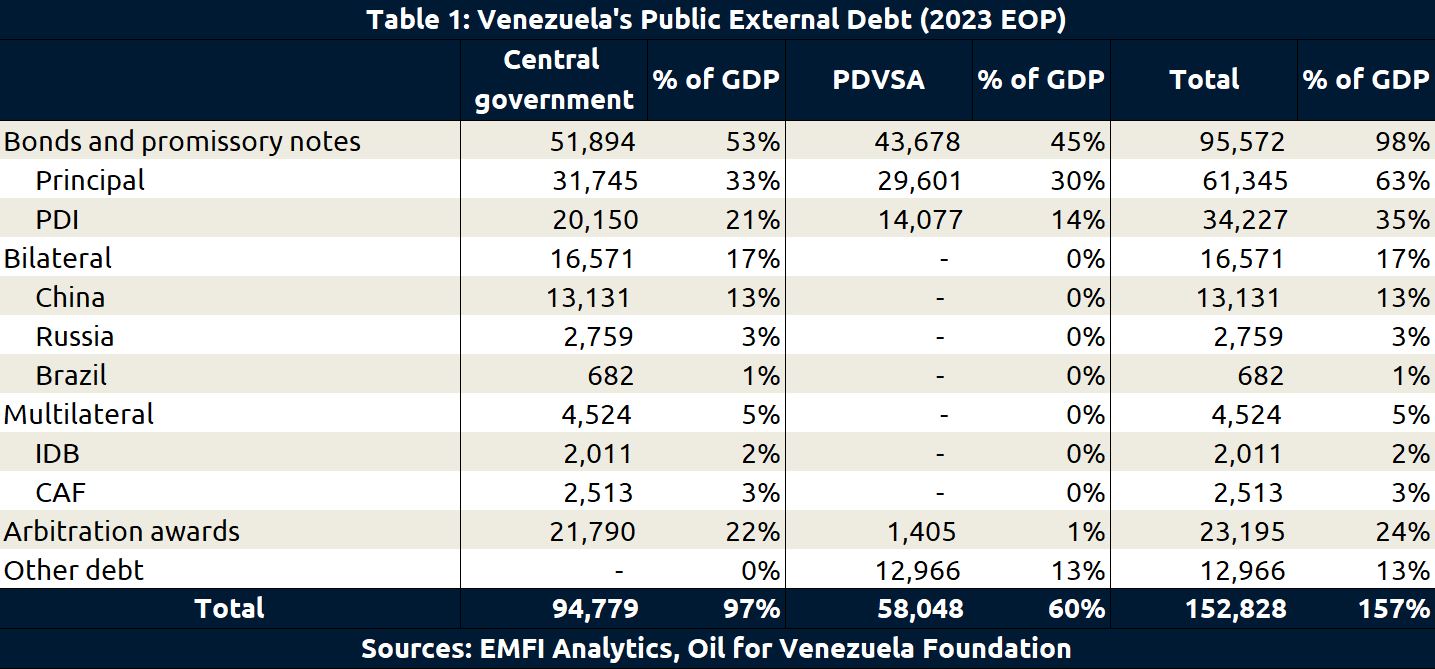

Looking at the data from EMFI Analytics (table 1), the estimated country’s stock of debt sits at $153 bn for the end of 2023; of which $96 bn is in the form of Eurobonds, $23 bn corresponds to arbitration awards, and $13 bn to oil-linked Chinese debt.

Assuming that the Venezuelan government were able to lift production to 1.5 million barrels per day over the next five years and oil exports doubled to just under $30 bn per year, the country’s GDP could rise from the current $98 bn to $123 bn. Thus, the debt/GDP ratio of 157% in 2023 would decrease to 124% by 2029 thanks solely to higher GDP growth – under the admittedly unrealistic assumption of no intermediate changes in gross debt – and debt service of around 16% of exports at the end of 2023.

Debt may also decrease in nominal terms over time, as the Venezuelan government pays some of its liabilities (Chinese debt, PDVSA commercial debt) and some of its creditors manage to recover from the country’s external assets (PDVSA 20 bond, Crystallex auction). In contrast, a full transition with larger FDI inflows could lead to a production recovery to 3.5 million barrels per day over a longer period, considerably reducing the required haircut.

Technical Considerations

With the allowance of secondary trading on Venezuela (VENZ) and Petroleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) bonds, attention now shifts to the potential rebalancing in the primary Emerging Markets benchmarks.

From July 2019 onwards, all VENZ/PDVSA bonds were excluded from the Emerging Markets Bond Indices (EMBI) due to the sanctions preventing buying in the US. This exclusion was quite unique, as the bonds technically remained in the index but with their weights reduced to zero. Importantly, this exclusion was a result of sanctions rather than the default that commenced in 2017.

The index provider’s initial notice also included a provision for a potential reversal if trading restrictions eased and liquidity improved. Upon re-entry, the estimated combined weight of the bond complex is projected to be approximately 0.73% in the EMBI Diversified and 0.86% in the EMBIG. These figures align closely with the weights prior to the reduction in 2019 (0.60% and 1.00%).

Anticipating when this might occur is challenging, and it’s probably best not to trade with an imminent rebalancing in mind. However, the recent increase in liquidity following the easing of sanctions, combined with the absence of a six-month expiration like the Oil trading sanctions, suggests a possible re-entry into the index in the near future.

It’s important to have this in mind: a rebalancing announcement will probably trigger further buying as EM dedicated funds will need to adjust their exposures.

Conclusion

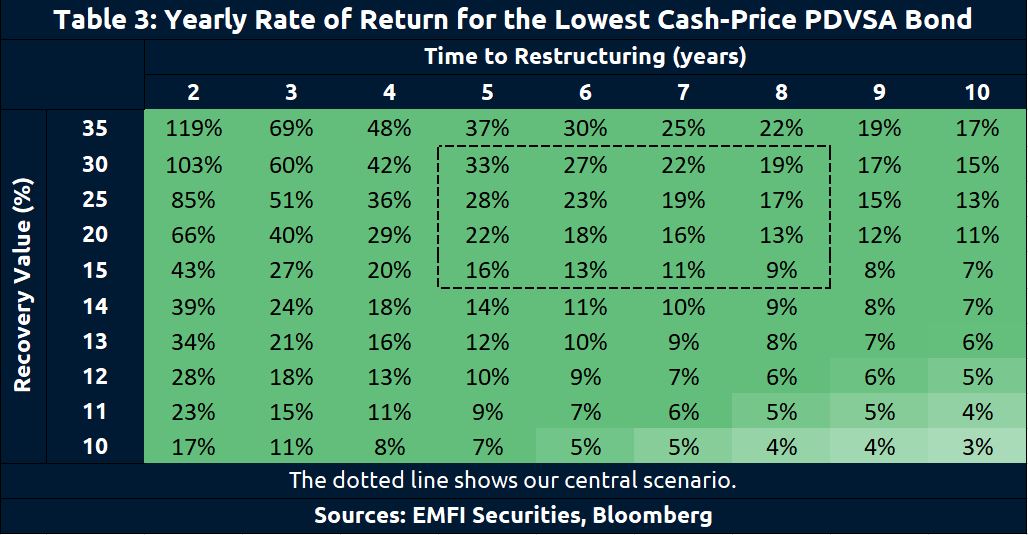

Will the recovery values of Venezuelan and PDVSA bonds be the same? There are several considerations here:

• The average coupon on Venezuela bonds is higher than on PDVSA bonds, which makes their Past Due Interest (PDI) higher in both absolute and relative value. Logically, a restructuring gives more to holders of bonds with higher coupons, but the overall value per dollar of claim will also be lower.

• Despite PDVSA being 100% state-owned, corporate asset stripping by the government is not in its interest. It is more likely, however, that Venezuelan bondholders may appropriate PDVSA assets abroad (see the case of CITGO and the legal concept of ‘alter ego’) to satisfy claims – we are watching how CITGO’s auction process develops.

• Some PDVSA bonds have weaker terms than the Venezuelan Sovereign Bonds (trustee structure or no Collective Action Clauses, which make it harder to use litigation in restructuring).

Strictly speaking, from a legal point of view (‘alter ego’ – see above), there seems to be no reason why Venezuela and PDVSA bonds should be treated differently. In practice, however, it depends on the negotiations with all creditors.

Finally, while recent developments are undeniably a step in the right direction, we remain sceptical that they will necessarily lead to a resolution to the Venezuelan long-lasting political crisis or a debt restructuring. Financial sanctions and Maduro’s lack of recognition by the US continue to prevent a conventional restructuring of the country’s external debt. Some heterodox partial restructuring strategies are theoretically possible but unlikely given the lack of incentives for the Maduro administration if no additional cash inflows are generated. We continue to like the Venezuelan recovery story, as there is still value, but it’s an entirely different trade now.