Mexico is back in the spotlight for global macro investors, with an election in June, closely followed by the US election not long after. The country is poised to benefit from deglobalisation as the US seeks to untangle complicated supply chains and reduce reliance on China.

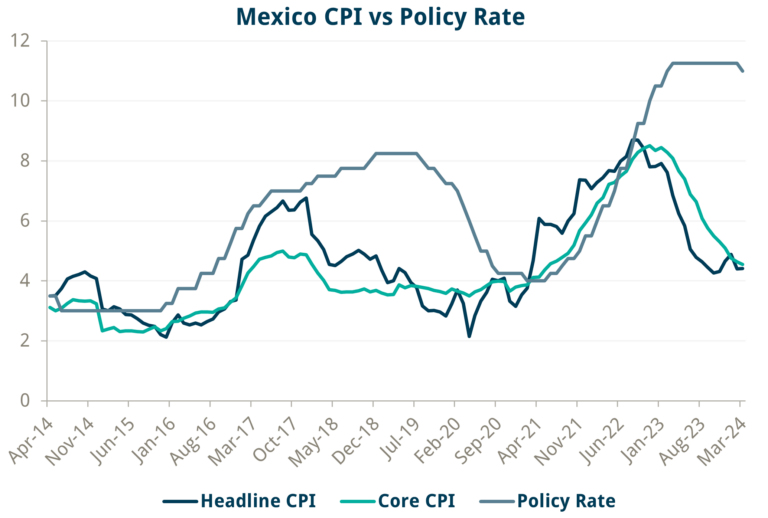

Interest rates may have reached a critical turning point as the central Bank of Mexico (Banxico) has just started to cut rates from a lofty 11.25% – the highest level since overnight rate targeting was established in 2008.

The rate hiking cycle started in June 2021, a full nine months before the US Federal Reserve. A similar story played out across Latin America where a history of inflation struggles means policymakers do not have the luxury of debating whether price rises are “transitory”. That cycle came to an end in March 2023, two years and 7.25% higher.

Before the cycle began, core CPI was 3.9% (with the average since 2020 at 3.8%), while headline inflation was 3.8% (compared to an average of 3.4% during the same period). Headline inflation peaked at 8.7% in September 2022 (when rates were 8.5%), with core CPI later topping out at 8.5% in November 2022 (by which point rates had been hiked to 10%) vindicating Banxico’s foresight in tightening monetary policy before inflation materialised.

Core CPI has since fallen significantly to 4.5% and has been declining steadily since January 2023. Headline inflation is 4.4% and has also been on a clear downward trend, albeit with a lurch higher in Q4 2023 as unfavourable weather sparked higher fruit and vegetable prices. This is a volatile but mean-reverting category within which we saw a dislocation of over three standard deviations, but it is normalising.

The question now is what happens to monetary policy?

Source: Trium Capital, Bloomberg, INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, National Institute of Statistics and Geography) and Banco de Mexico

The fall in inflation has left Mexico with one of the highest levels of real rates in the world. The ex-ante real policy rate is around 7.5%, which is a full 3% higher than in previous cycles. Moreover, Banxico’s own estimates of the neutral real rate is between 1.80% and 3.40%, meaning that current rates are over twice as high as the top end estimate, and therefore very restrictive in terms of economic activity.

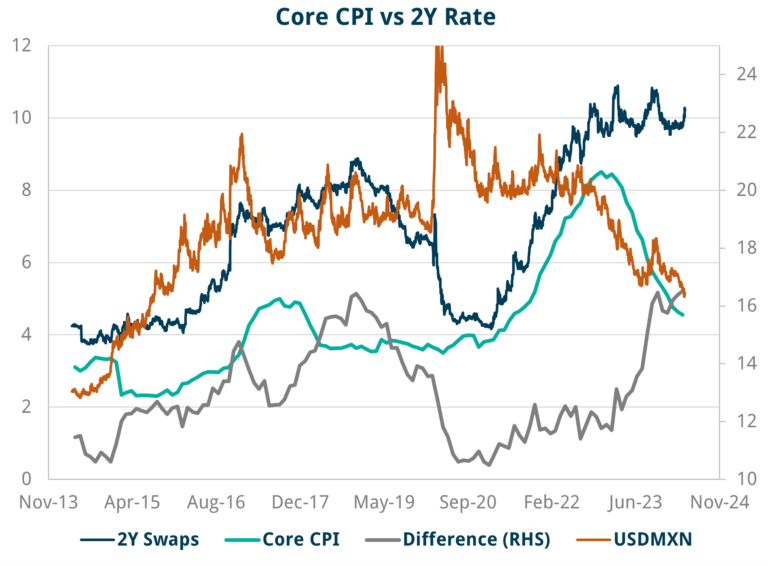

There has been a marked change in tone over the last two Banxico meetings, as the discussion among committee members has quickly shifted from maintaining the target rate in December, to assessing the possibility of an adjustment in February, before then delivering a cut in March. There has, however, been much insistence by Banxico that inflation risks remain to the upside, that this is not yet the beginning of a cutting cycle, and that they will make their decisions based on available information at the time. These comments, together with the backdrop of the recent sell-off at the front end of the US curve, have driven two-year rates in Mexico back to Q3 2023 levels – higher than they were before the recent cut.

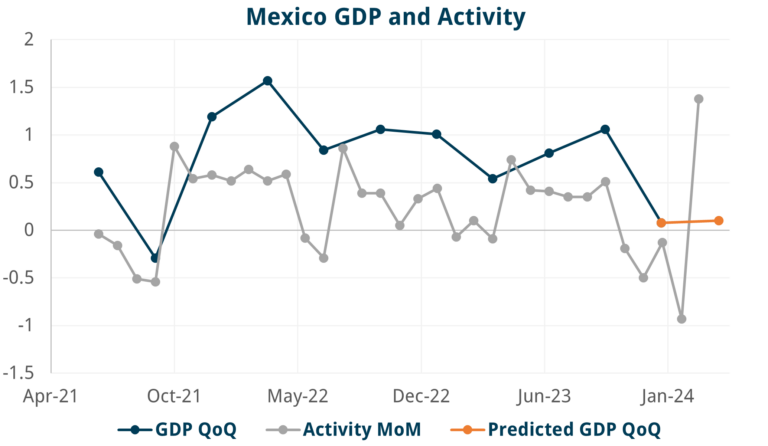

The case for cuts is supported by slowing economic activity. The monthly economic activity indicator surprised to the upside for February with 1.38% MoM compared to a 0.50% analyst expectation, but that comes after four consecutive negative prints since October. Furthermore, the January figure was also revised down from -0.63% to -0.93%. GDP came in at a meagre 0.1% for Q4 2023 (compared to an expectation of 0.4%), and despite the stronger than expected February figure the more recent activity data is consistent with a GDP growth of 0.1% QoQ.

Source: Trium Capital, Bloomberg, INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, National Institute of Statistics and Geography

This combination of slower activity and the easing of inflationary pressures explains the 25 bps cut in March – but the fact that the market is pricing higher rates than before the cut is counterintuitive. It seems that participants are focusing more on the hawkish rhetoric of the Mexican central bank, while extrapolating the consistently strong US CPI numbers and related repricing of the front end of the US curve. Furthermore, this is taking place in an environment of very crowded longs in bonds and received positions in swaps. Many market participants are being stopped out as rates march higher, which usually brings good opportunities.

One of the attractions of the Mexican fixed income market is that it can be prone to overreaction. Back in 2017, we saw a sizeable 75 bps move lower in two-year rates as the market digested the implications of Trump election and forecasted the end of the hiking cycle at 7.0%. Participants started to price cuts only to see it all unwind sharply towards the end of the year on a combination of overblown worries about the election of ‘AMLO’, and legitimate concerns around the NAFTA renegotiation. Banxico was forced to start hiking again after five months on hold to prop up the tumbling Peso, eventually ending the cycle in December 2018 with rates at 8.25%.

The market was again tempted into positioning for lower yields at the start of last year, when front-end rates reached all-time highs, thinking that Banxico would cut. But investors were caught off-guard by an extended cycle, fuelled by a repricing of the US curve and robust remittance flows, which saw them an additional 75 bps of hikes enacted in 2023.

However, Mexico now has much lower inflation, significantly slower growth, and a central bank that has actually cut. After a false start, now is the time. The positioning washout will soon be over and will provide very attractive entry levels.

Elevated US CPI is somewhat idiosyncratic, and we believe that markets should be wary of assuming that the year-to-date revaluation of the path ahead for US rates (with the market having shifted from pricing six cuts this year to less than two) will automatically lead to Mexican rates being held steady for a prolonged period. Examples of policy divergence can be seen in the current Brazil easing cycle, and in Peru cutting rates by surprise last week (11 Apr 2024).

In our opinion, the argument about the hawkish Banxico minutes is misplaced. Could it mean this is not the start of a cycle, and that rates might be held at the May meeting? Sure. Is it all that relevant? We would argue not. This growth slowdown is also happening with a record deficit and very high spending which is projected to be reduced next year, further dampening growth. If Banxico does keep rates on hold in May, there will still be more cuts to come.

The Opportunity

With two-year rates at 10.35%, there is tremendous potential upside in the Mexican front end. The last time that the disconnect between core CPI and two-year rates was so extreme was in 2017, when the market rapidly shifted from pricing cuts to getting hikes (see Chart 3 below). This means the central bank could cut in excess of 2% to sustain activity, and still have very restrictive monetary policy.

Banxico’s mandated goal is currency stability. In 2017 the geopolitical and fiscal situation triggered a devaluation of the Peso and so the Bank was forced to hike despite already high real rates. It is a very different story today. The Peso has been exceptionally strong, having rallied 10% against the dollar since the last hike in March 2023, and 20% since mid-2022.

Last time we saw a massive 4.25% decline in two-year rates and, in our view, we will likely see a move of a similar magnitude play out again.