In June we explained why we were constructive on gold. We outlined the deep relationship between gold and real interest rates and showed how that relationship has appeared to change as the marginal buyer shifted from Western investors to Emerging Market central banks.

Much of the central bank buying is secretive. While the increase in officially declared purchases has been relatively modest, there are fingerprints to suggest that EM central banks have been mopping up supply though other channels. In particular, Chinese buying outside of the central bank has stepped up significantly as other state institutions have tapped the market.

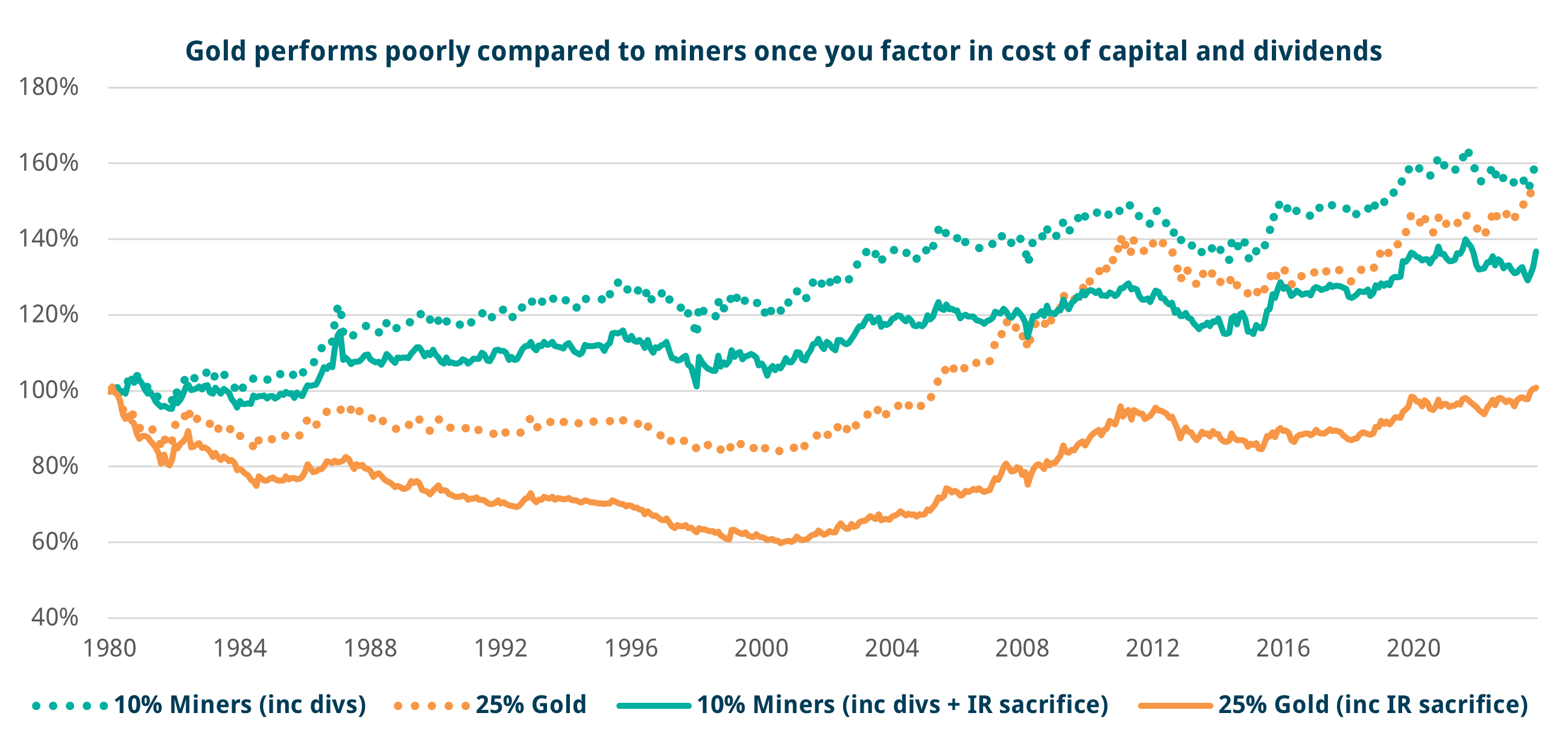

While we laid out the case for why we like gold, our current positioning is via gold miners rather than physical gold. We think investor concerns about the miners are misplaced when making a proper comparison taking all relevant factors into account. There are two major reasons why long-term historical analysis comparing physical gold to miners is often flawed.

Firstly, there is a lack of accounting for dividend accrual on the miner side. When you compare one equity market to another, or two individual stocks, it does not matter hugely so long as both have similar dividend payouts. This is especially true for short-term comparisons. When comparing gold to gold miners, however, you are comparing a zero-payout asset to one with high cashflows, which becomes increasingly important as you extend the period of analysis.

Secondly, gold miners have a significantly different volatility profile to that of the metal. The risk and potential return associated with gold equities is about 2.5x that of gold. When interest rates are low, the opportunity cost of bigger position sizes is also low. When rates are higher, taking a much larger position in physical gold (e.g. 25% NAV) rather than a smaller, but risk-equivalent, position in gold miners (e.g. 10% NAV) sacrifices an extra 15% of portfolio assets that can’t sit in high-yielding bills. Over the long term this adds up. Investing via gold futures or other vehicles does not change the arithmetic, as buying and rolling futures incurs a running cost that exceeds the pick-up from investing the unencumbered cash in bills.

When you correct for these factors and carry out a long-term analysis, the perceived structural outperformance of gold over the miners disappears.

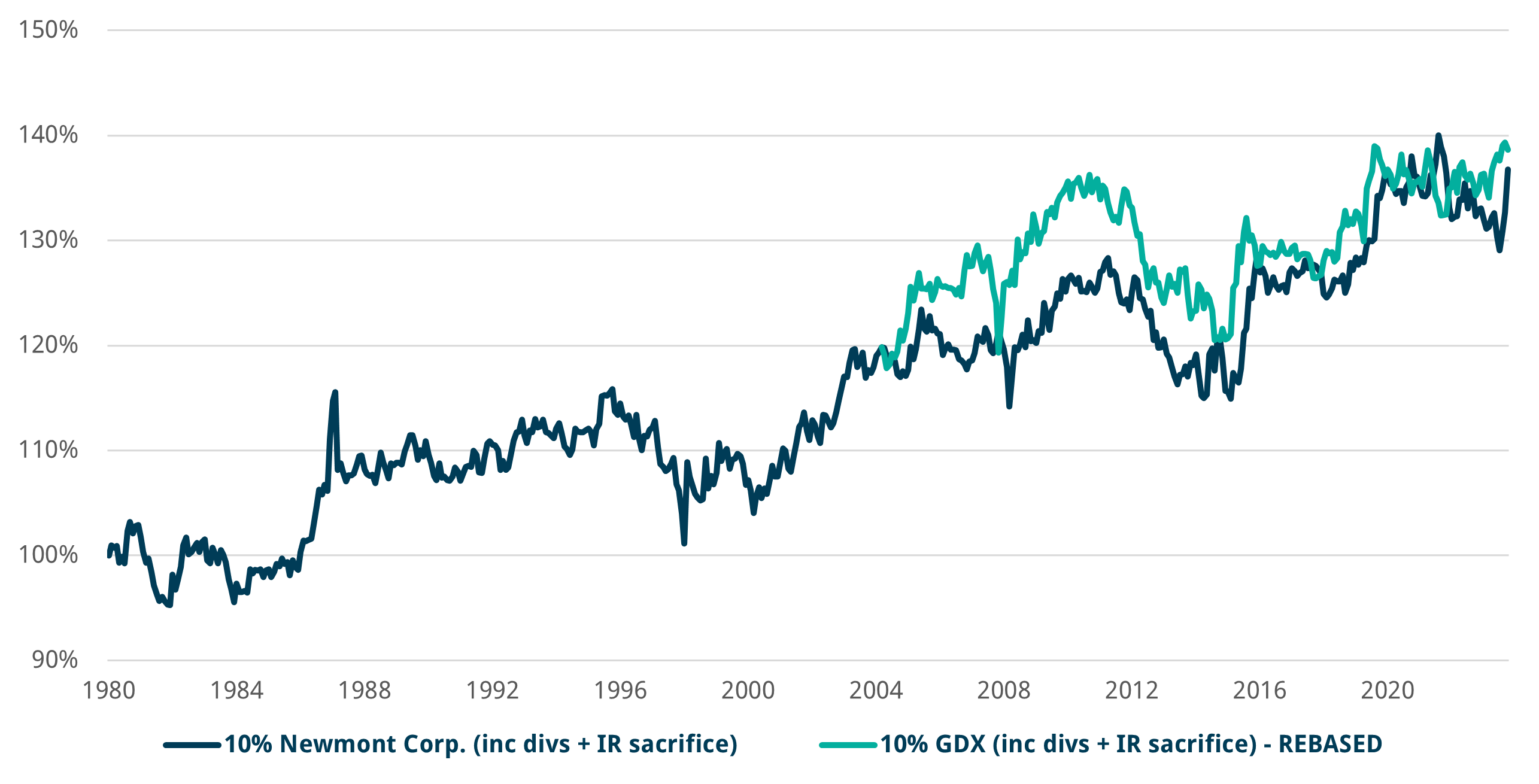

We have run our analysis (Chart 1) from 1980 onwards using Newmont; the largest listed miner and the gold stock with the longest single history. Our analysis compares the performance of a 10% NAV position in the miner with a risk-equivalent investment of 25% NAV in the metal (this risk ratio is fairly stable over time, and we hold at 2.5x for simplicity). Before accounting for interest rate sacrifice, the miner and the metal have delivered similar returns of 62% and 58%, respectively, since 1980.

Due to the much larger notional size in gold relative to the miner, the interest rate sacrificed in holding the metal is significant, all but eliminating positive returns accrued over the period (realised return of just 1% since 1980). The return on the miner is also meaningfully reduced to 38% but is far less impacted than the metal, hence running an RV trade long the metal relative to the miner would have resulted in a 28% loss over the period.